God is a concept found in various religious and spiritual traditions around the world. While the specific characteristics and beliefs about God vary, the general understanding is that God represents a supreme being or ultimate reality. God is often described as the creator of the universe, possessing qualities such as omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence.

Many religions view God as a source of moral guidance, love, and compassion. Different names and forms are attributed to God, reflecting cultural and theological diversity. Devotion, prayer, and worship are common ways in which believers seek to connect with and express their relationship to God. Ultimately, the nature of God remains a deeply profound and subjective subject, shaping the beliefs and practices of countless individuals and communities throughout history.

Who is God?

God’ is a widely recognized term that represents the essence of a higher being existing beyond our world, the ultimate creator of all known existence, and the overseer in conjunction with subordinate divine entities (angels). In Greek, theikos, meaning “divine,” encapsulates the idea of possessing god-like attributes or power. Theology, therefore, delves into the exploration of God’s nature and the intricate dynamics of God’s relationship with humanity.

The English word ‘god’ originated from a German expression found in the 6th-century Christian Codex Argenteus, known as gudan, which conveys the act of summoning or invoking a higher power. In Western traditions, ‘God’ is specifically associated with the God of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, collectively known as the three Abrahamic faiths. All three religions assert that this divine entity revealed himself to the ancient patriarch, Abraham. In English Bibles, the capitalization of the ‘G’ in ‘God’ serves to distinguish this supreme being from all other gods.

Ancient Cultures

In ancient times, diverse cultures envisioned the universe as a three-tiered realm, consisting of the heavens, the earth, and the underworld. The heavens were believed to be the dwelling place of the gods, while the earth was designated for humans, and the underworld served as the realm of the deceased. It was believed that gods possessed the ability to transcend these realms, exerting their influence across all three levels.

Within many ancient tribes, a local deity held a prominent position as the progenitor of their clans. Some cultures further embraced the concept of a supreme god or goddess, or a king/queen of the gods, who governed various aspects of the universe with their diverse array of powers.

Ancient religions also featured creation myths that provided explanations for the origins of the universe, often depicting its emergence from a primordial state of chaos. These myths also shed light on the creation of the first humans and the establishment of human society. As bearers of divine authority, these stories served to validate contemporary law codes, encompassing rituals, behavioral norms, and gender roles. The laws were considered sacred, as they were believed to have originated from the gods.

One of the primary methods through which ancient peoples sought communion with their deities was through divine possession, a practice commonly known as divination. Oracles, both individuals and specific locations, served as conduits for divine messages, with a deity speaking through them while in a trance-like state. In the Jewish tradition, the prophets fulfilled a similar role, being vessels through which God communicated messages to the people. In written texts such as the Bible, the words of God are distinguished by the introduction, “Thus says the Lord,” and are often structured and indented like poetry.

Also Read: Divine Deities

The God of Israel

The God of Israel is portrayed in the book of Genesis as the supreme deity of the emerging nation of Israel. According to Jewish Scriptures, this deity is credited with creating and governing the known elements of the universe and everything on Earth. What sets the God of Israel apart is the way in which this deity acts independently, without a female consort, solely through speech. In fact, Genesis 1:3 states, “And God said, ‘Let there be light.'” Interestingly, the concept of creation through speech is not exclusive to Israelite beliefs, as ancient Egyptian religion also attributed this ability to their creator god, Ptah. Moreover, the God of Israel is responsible for the creation of the first human couple, Adam and Eve, who were commanded to procreate and populate the Earth.

A pivotal moment in Genesis occurs in chapter 12, known as the call of Abraham, who hails from Ur in Mesopotamia. Abraham is destined to become the patriarch of a great nation, as signified by his name change from Avram to Abraham. Additionally, he is promised the prosperous land of Canaan, which would serve as an abundant dwelling place for his clans and livestock. The descendants of Abraham were assured protection and prosperity as long as they honored and obeyed the God of Israel. Notably, circumcision was introduced as a divine commandment to Abraham and his progeny, symbolizing their distinct identity and setting them apart from other nations.

In ancient times, people forged contracts with their deities, outlining the responsibilities and obligations of both parties involved. From the Hebrew term “to cut,” the concept of a “covenant” emerged, representing a contractual agreement accompanied by the ritualistic act of dividing animal sacrifices while pledging an oath to a deity. The God of Israel is depicted engaging in various covenants with his people, including those with Noah, Abraham, Moses, and King David. These covenants solidified the relationship between the God of Israel and the Israelite community, establishing a framework for mutual obligations and divine protection.

El

In ancient texts from various regions, the term “el” (plural: elohim) held significant meaning, representing divine powers in Hittite, Ugaritic, paleo-Hebrew, Canaanite, and Aramaic contexts. El was often regarded as ‘the god’ in order to distinguish it from other deities and was frequently associated with the act of creation. Moreover, El was often combined with specific attributes. For instance, in Genesis 17:1, during Abraham’s second encounter with God, this divine being was referred to as El-Shaddai, meaning “God almighty.” Similarly, in Genesis 14:18-20, Abraham received a blessing from Melchizedek, the king of Salem and a priest of El Elyon (“the most high” God). Consequently, those who followed this deity became known as Israelites, as seen in Genesis 32:28: “Your name will no longer be Jacob, but Israel because you have struggled with God and with humans and have overcome.”

The term “Jews” emerged more commonly during the Persian occupation in the 6th century BCE, originating from “Yehudi,” which denoted individuals hailing from the kingdom of Judah. Notably, during the reign of King Ahab and his wife Jezebel in Northern Israel (871-852 BCE), the deities worshipped by Jezebel’s family, namely the ba’als (Levantine and Canaanite gods), held prominence. However, through the efforts of the prophets Elijah and Elisha, as documented in the book of Kings, the God of Israel ascended to the status of a national deity. The concept of God as a universal entity is eloquently expressed in Isaiah’s words: “Do you not know? Have you not heard? The Lord is the everlasting God, the creator of the ends of the earth” (40:28).

Polytheism & Monotheism

Polytheism and monotheism have been polarizing concepts since the Enlightenment, categorizing world religions based on the worship of multiple gods or the belief in a single deity. However, these terms pose challenges as descriptors because they were not commonly used in ancient times. It would be more accurate to say that ancient civilizations embraced religious pluralism. People in those times did not express their beliefs or faith (known as “pistis” in Greek) in the same way we do today. Instead, they believed in their gods and focused on correctly performing rituals and sacrifices, as passed down from the gods to their ancestors. Ancient monotheism did not exist as a concept, and all ancient people, including the Jews, were polytheistic in this sense.

The ancient Jewish worldview included a heavenly hierarchy of powers, featuring a divine court comprising “sons of God,” angels, archangels, cherubim, and seraphim. Jews also acknowledged the existence of lower divinities known as demons and introduced the concept of a fallen angel, which eventually evolved into the figure of Satan, the Devil.

In the Jewish Scriptures, the God of Israel, as the original creator, took responsibility for the existence of “other gods” and consistently acknowledged the gods of other nations. For example, Deuteronomy 6:14 warns against following other gods, while Psalm 82:1 states, “God presides in the great assembly; he renders judgment among the gods.” During the Jews’ exodus from Egypt, their God engaged in a battle against the gods of Egypt to demonstrate control over nature. This narrative would hold little meaning if the existence of these gods was not recognized.

The foundational story supporting the notion of Jewish monotheism revolves around Moses receiving the ten commandments from God on Mt. Sinai. As stated in Exodus 20:2-3, Moses heard the words, “I am the Lord your God… You shall have no other gods before me.” It is important to note that this commandment does not imply the nonexistence of other gods; rather, it strictly prohibits the worship of any deity other than the God of Israel. In the ancient world, worship was closely tied to belief and veneration, often involving sacrificial rituals. While Jews were allowed to pray to angels and other celestial powers, sacrifices were reserved exclusively for the God of Israel. This commandment served as a significant point of distinction between Jews and other traditional ethnic cults. Moreover, it was reinforced by the prohibition on creating any images resembling heavenly, earthly, or aquatic beings, as mentioned in Exodus 20:4.

Yahweh

Yahweh, the sacred name of God, was revealed to Moses when he encountered a divine presence on Mount Sinai. In response to Moses’ inquiry about his name, God declared, “I am who I am” (Exodus 3:14). The term “Yahweh” derives from the four consonants in this declaration (YHWH) and is also known as the Tetragrammaton.

In the ancient Hebrew language, vowel sounds were not written down, and letters were added later. The phrase “I am who I am” can be understood as an action verb, as it originates from the first person singular of the verb ‘to be’ in Hebrew, ehyeh asher ehyeh. This name signifies a God who acts and intervenes in the earthly realm of his people. Moreover, the name “I am” denotes self-sufficiency and independence, reflecting the primordial creator who relies on no other powers.

Interestingly, the name Yahweh appeared earlier in an inscription in Egypt, commemorating the victories of Pharaoh Amenhotep III around 1400 BCE. This inscription mentioned “enemies from the land of Shasu of Yahweh,” with Shasu referring to a specific group of nomads that may have included the Israelites. This suggests that the adoption of Yahweh as a deity by these nomads predates the story of Moses. Additionally, a stele erected by the Moabite king Mesha in the 9th century BCE boasted of his victory over the king of Israel and his capture of the vessels of Yahweh.

Overall, Yahweh is the sacred name of God, revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai. Its significance lies in its connection to divine action, self-sufficiency, and the historical presence of Yahweh among specific nomadic groups, potentially including the Israelites.

Jerusalem & Temple Worship

During the Iron Age (1200-600 BCE), the Israelites formed a tribal confederation consisting of the descendants of Jacob’s twelve sons, as described in the books of Joshua and Judges. In those times, the Ark of the Covenant, containing the tablets of the law, was safeguarded in a portable tent shrine, known as the Ark of the Covenant, as established by Moses during the wilderness years. To prevent any sense of envy or dominance among the tribes, different tribal sections took turns guarding the tent at various cult sites.

In the reign of King Solomon (970-931 BCE), Jerusalem, which had been conquered by his father, King David, became the site of the first temple. It was King Josiah (640-609 BCE) who is credited with bringing about a significant reform in the worship practices by centralizing them solely at this temple and directing them exclusively to Yahweh. Scholars argue that it was during this period that Deuteronomy 6 was incorporated, eventually becoming the fundamental prayer of Judaism known as the Shema Yisrael: “Hear, O Israel, Yahweh is our God, Yahweh is one.”

The Ark of the Covenant was transferred to the Holy of Holies, the innermost sanctuary of the Temple. Moses was told, “There, above the cover between the two cherubim that are over the ark of the covenant law, I will meet with you and give you all my commands for the Israelites” (Exodus 25:22). The Ark symbolized the presence of God in the temple, serving as either His throne or footstool. It was this divine presence that imbued the temple with sanctity, necessitating adherence to the purity regulations outlined in the book of Leviticus when approaching the sacred space.

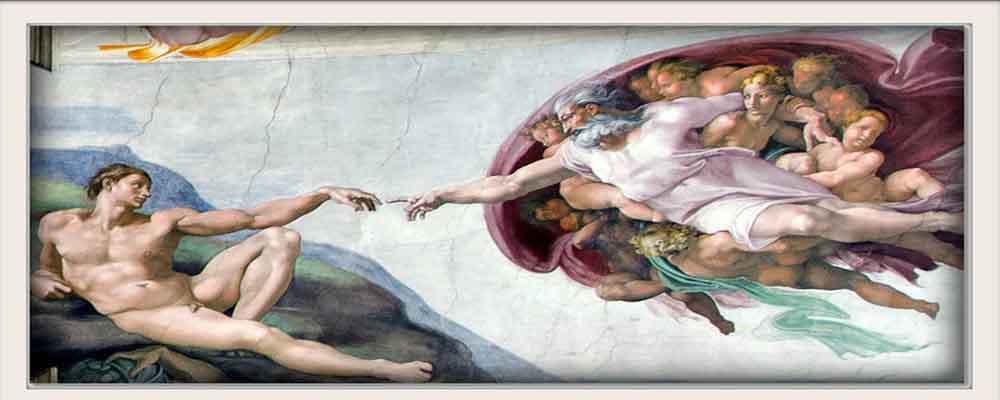

Appearance & Attributes

The God of Israel is portrayed in a unique manner, abstaining from any visual representation such as statues or images. However, this does not preclude the use of symbolic or literary analogies. Interestingly, pre-reform depictions of Yahweh, especially in Northern Israel, often incorporated a bull image (as seen with the golden calves of Jeroboam in 1 Kings), symbolizing fertility.

In Genesis 1:26-27, a passage states:

“Then God said, ‘Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.’ So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.”

A more contemporary interpretation of this passage associates “image” with function. Just as God ruled over all creation, men and women were intended to rule as devoted representatives of God in caring for the Earth. Considering the gender and gender roles prevalent in ancient times, the God of Israel was consistently described as male. There are numerous anthropomorphic descriptions attributed to God, such as the face or hand of God.

Rather than literal depictions, common attributes assigned to God include omnipotence (all-powerful), omniscience (all-knowing), and omnipresence. The concept of omnipresence aligns with the notion of transcendence, representing the ability to traverse the spatial realms of the known universe. Additionally, the concept of immanence acknowledges that at times, the God of Israel manifested Himself on Earth in various ways, either to rescue or discipline His people. God utilized prophets to call for repentance whenever they had sinned or neglected the commandments.

Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism underwent significant changes following the conquests of Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE), as Greek culture, government, and religion permeated the Eastern Mediterranean. Educated Jews found themselves able to engage with the various schools of Greek philosophy. Philosophers during this period embraced the idea of an original high god existing beyond the confines of the physical universe and employed allegory and metaphor as literary devices. This supreme being, as a pure and benevolent essence, was not directly responsible for creation but rather emanated lower powers who assumed that role. The unity of this supreme god permeated the entire cosmos, encompassing nature, materiality, and the human soul. This interconnectedness was achieved through the divine aspect of logos, often translated as “rationality” or “word.”

One of the prominent figures in Hellenistic Judaism was Philo of Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher who wrote in the early decades of the 1st century CE. Philo presented Judaism through the lens of Greek philosophical principles, asserting that the God of Israel was the same one high god acknowledged by the Greeks. Employing allegory, Philo depicted Moses as the embodiment of the logos, responsible for providing a rational and logical framework through the Mosaic Law.

Christianity: The Emergence of a Revolutionary Faith

In the tumultuous decades of the 1st century CE, a figure named Jesus of Nazareth emerged as a prophetic voice, heralding the imminent arrival of God’s kingdom on earth. Challenging the authority of Rome, Jesus met a tragic fate, crucified as a traitor under the watch of Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator. However, his followers soon claimed that he had triumphantly risen from the dead and ascended to the divine realm by God’s side (Acts 7).

The earliest traces of what would evolve into Christianity are found in the letters of Paul the Apostle, composed during the 50s and 60s CE. Once a Pharisee, Paul underwent a profound experience—a heavenly vision of Christ (the Greek term for messiah, Christos)—and believed he was called to be the apostle and messenger to the Gentiles, encompassing non-Jewish communities. The prophets had foretold that Gentiles could partake in God’s kingdom on earth without adopting the physical markers of Jewish identity, such as circumcision, dietary laws, or Sabbath observance. However, Paul’s communities were required to abandon traditional idolatrous sacrifices to other gods. It is important to note that, at this stage, monotheism was not fully established. Paul acknowledged the existence of other deities, chastising them for interfering with his mission. Yet, sacrifices to these gods were no longer valid within Paul’s conception of salvation.

Paul introduced a groundbreaking innovation to Jewish traditions. He asserted that Christ, who had existed alongside God since creation, had humbled himself by assuming human form and sacrificially atoning for the original sin of Adam, which brought death into the world (Romans 5). Christ was bestowed with “the name that is above every name,” including the sacred Tetragrammaton, Yahweh. In this context, the act of bowing before divine images was metaphorically applied to Jesus, emphasizing his worthiness of worship (Philippians 2). Paul masterfully employed a Jewish notion of God’s selflessness, illustrating how God manifested in the earthly Jesus. The Gospel of John, in its opening verses, further developed this concept through the divine logos, solidifying the doctrine of the Incarnation, wherein Christ took on human flesh.

The schism between Christianity and Judaism emerged in the 2nd century CE when Christian leaders, disconnected from Jewish ethnic ties, merged God’s scriptural traditions with elements of philosophical concepts about the supreme deity. During this time, Christians faced persecution from Rome due to their refusal to participate in the state and imperial cults. Christians sought to attain the same exemption that the Jews had received from Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE), asserting themselves as the true heirs of God’s covenant with Israel. Through allegorical interpretations, the Church Fathers presented an intricate tapestry, contending that every aspect of Israel’s history and narratives pointed toward a pre-existent Christ. What distinguished Christians from Jews was their liberation from the literal observance of the Mosaic Law, as God had established a new covenant that revolutionized traditional practices. Simultaneously, Christianity distanced itself from the prevailing culture by denouncing all forms of idolatry.

Trinity

During the early days of Christianity, the concept of expressing the oneness of God while acknowledging the divinity and worship of Christ sparked ongoing debates and conflicts. Arius, a presbyter in Alexandria, taught that if one believed that everything in the universe was created by the God of Israel, then Christ must have been created by Him as well, implying that Christ was a subordinate creature. Riots broke out in some cities due to this teaching, prompting Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) to convene the First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. In an effort to maintain the Jewish tradition of worshipping a singular God, Christians developed the concept of the Trinity, which elucidated the relationship between God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit.

The crux of the debate centered around two choices: was Christ homo-iousios, possessing an essence similar to the Father’s, or was he homo-ousios, of the same substance and identical to the Father’s? The Council ultimately chose the latter, affirming that God and Christ shared the same essence (substance) and that Christ was a manifestation of God Himself on earth. With the Bishops present, Constantine had them compose what would later be known as the Nicene Creed (derived from the Latin word “Credo,” meaning “I believe”). This marked an innovative development, as in the ancient world there was no centralized authority dictating beliefs. As the leader of both the state and the Church, Constantine now possessed the authority to mandate its acceptance among all Christians. In a system where traditional sacrifices and rituals had been abandoned, belief became a paramount concept.

In traditional Judaism, the “spirit of God” denoted the way in which God empowered individuals and actions, such as the spirit that animated Adam upon his creation and the divine possession experienced by prophets. From the inception of the Christian movement, believers had encountered this power as gifts from God, enabling them to prophesy, teach, speak in tongues, heal, and even resurrect the dead. The Nicene Creed upheld the oneness of God while acknowledging three aspects: God the Father, Christ the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

God in Islam

God in Islam emerged as a reform movement incorporating elements from Judaism and Christianity. The Prophet Muhammad received revelations in the 6th century CE, which were eventually compiled into the sacred text known as the Quran. The term “Allah” in Arabic is likely derived from “al-ʾilāh,” meaning “the God,” and it distinguishes this deity from others.

The central concept in Islam is tawhid, which emphasizes the oneness of God. This is expressed in the shahada, one of the pillars of Islam, which states that there is no god but God and Muhammad is His prophet. The Quran reinforces this belief, stating, “Say: He is God, the One; God, the Eternal, the Absolute; He begot no one, nor is he begotten; Nor is there anyone equivalent to him” (112:4). Islam strictly prohibits any form of idolatry, known as shirk, and does not recognize a formal priesthood, as there are no intermediaries between God and humans. Instead, spiritual guides called imams to provide guidance within the community. The Islamic faith acknowledges the existence of angels as messengers of God and upholds the honor of traditional patriarchs and prophets, with Muhammad being the last prophet.

Although masculine pronouns are used in Arabic, God in Islam is beyond gender and physical attributes. The Quran states, “There is nothing whatever like him, and he is the One that hears and sees [all things]” (42:11). The concept of Qadim, meaning “ancient,” implies eternity without a beginning or end, making it impossible to apply human boundaries or measurements to God. Hence, Islam maintains a prohibition on anthropomorphic descriptions, idolatry, and images, as these are inadequate attempts to describe the perfect and unique nature of God. Allah, as the uncaused cause, is the ultimate source of existence and created everything out of nothing. The most commonly used attributes to describe Allah are “compassionate” and “merciful.” Similar to Judaism and Christianity, Islam anticipates a future reign of God on earth and a final judgment.

Frequently Asked Question

What is the full meaning of God?

The term “God” does not have a specific full meaning, as it is often used as a title or designation for a supreme being or ultimate reality in various religious and spiritual contexts. It represents the concept of a divine entity or higher power.

Who is the most powerful god?

Different religions and belief systems have different conceptions of the most powerful god. In Hinduism, Lord Shiva is often revered as the supreme deity, while in Christianity, God is considered the all-powerful creator and sustainer of the universe. The notion of the most powerful god may vary depending on individual beliefs and cultural perspectives.

How is God our Father?

In many religious traditions, the metaphorical notion of God as a father is used to convey a sense of loving care, guidance, and protection. This concept emphasizes the belief that God nurtures and provides for humanity as a father would for his children. It signifies a relationship of love, compassion, and familial connection between the divine and humanity.

Who is the first God in the world?

The idea of the first God varies across different mythologies and religious beliefs. In some polytheistic traditions, such as ancient Mesopotamian or Egyptian religions, there are multiple gods without a clear first deity. In monotheistic religions like Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, God is considered the eternal and uncreated being, with no predecessor or beginning.

What’s God’s real name?

The concept of God’s name varies among different religions and cultures. In monotheistic traditions like Judaism, the divine name is often represented as YHWH, commonly referred to as the “Tetragrammaton.” In Islam, the Arabic term “Allah” is used as the name for God. It’s important to note that these names are understood as human attempts to refer to and address the divine, and they may carry deep cultural, historical, and religious significance.